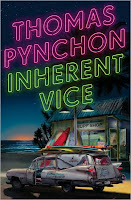

Although it did not take me very long to read Thomas Pynchon's newest novel, "Inherent Vice," it has taken me a long time to absorb it and develop anything coherent to say about it. Coming in at just over 350 pages, it's Pynchon's shortest work in quite a while, and, maybe as a result, it is also his most coherent and readable. (Of course, considering Pynchon's prior work, everything is relative - "Inherent Vice" has already produced a pretty comprehensive wiki.)

The best way to sum up the book is: Raymond Chandler noir crossed with an acid trip.

The book starts with the protagonist - Doc Sportello, a private detective who spends most of his time high - being approached by an ex-girlfriend who suspects that her boyfriend's wife (read between the lines there) is up to something fishy. Of course, a day or two later, there's gunfight which ends with the boyfriend - a highly influential real-estate developer - as well as the ex-girlfriend missing and his bodyguard dead. Stoner's logic leads Sportello to try to unravel this mystery despite the fact that he knows he will not be paid, which leads to even more mysteries and subplots which include an undead saxophone player, a brainwashing center disguised as a rehab hospital, a half-developed futuristic commune in the Nevada desert (which might also be a portal to other dimensions), an "Atlantis" myth for the Pacific, and the "Golden Fang" which is simultaneously a building, a dental group, a drug cartel, and a boat. In the end, nothing is really resolved except a mystery which at the beginning is a passing comment. Yet, in true postmodern fashion, th

ere is a sense that "all's well that ends well" because none of the major characters are dead and life goes on.

Although the complexities of noir fiction are nothing new to Thomas Pynchon (see "The Crying of Lot 49"), this book is much more "real" than his prior work. It is set in a (mostly) real place - 1970 Los Angeles - and features (mostly) real locations - such as Pink's and the Original Tommy's. Yet, these places are rendered as unfamiliar because the narrator is inherently unreliable due to his drug vice (pun intended). So much of Sportello's time is spent drinking, smoking weed, or dropping acid th

at it's sometimes hard to tell which parts of the story are the true, underground conspiracy and which are just waves of drug-induced paranoia. The sense of real provided by the setting, then, becomes an illusion.

Almost humorously, Pynchon seems to reference his real life elusiveness through the character of Coy Harlingen. When we first hear about Coy, we find out that he was a saxophone player for the band The Boards who just recently (in book time) died of an overdose. Yet, as the plot unravels, he keeps popping up everywhere - even being shown on television getting arrested at a Richard Nixon rally. Eventually, Coy even re-joins his old band, but nobody recognizes him. His logic, then, is to hide in plain sight: nobody recognizes him because they all think he's dead. Anybody who s

uspects that he faked his own death would never think to

look for him at the same places doing the same things he previously did. Coy, in a way, comes to represent Thomas Pynchon - he hides in plain sight. Pynchon has admitted doing normal, everyday things. He even recently had lunch with Salman Rushdie and has appeared (dubiously) on "The Simpsons". Yet, he's managed to maintain his anonymity despite his celebrity. Although his books always make the bestseller list and his name is synonymous with postmodernism, his face is a paper bag with a question mark on it. He is a voice, a book cover, a name. Yet, he is also human and does human things. He is "dead" t

o the world, yet he lives the way he would if he were "alive."

I'm still not quite sure I understand all of what "Inherent Vice" was really about (assuming it was about anything - which is a valid point in Pynchon's work). At once the novel seems both nostalgic for 1970 while at once pointing to its hollowness. Doc starts out to solve one mystery, becomes a part of another, and helps to solve a third one while the original one plays itself out - and so he is both a major player and a completely helpless pawn. Coy is both stone cold dead and vibrantly alive. So, what are we to make of these contradictions? The closest we get to a solution comes from the character Bigfoot Bjornsen when he says (which could be echoed by Pynchon himself):

"If I didn't know, I would never admit it to you. And if I did know, I would never tell you."

No comments:

Post a Comment