Friday, January 29, 2010

Manhood for Amateurs

Thursday, January 28, 2010

The Gunslinger

Ever since I was a little boy, I’ve always gone to Steven to get my haircut. And as long as I can remember talking to Steven about books, I’ve known that Steven is a Stephen King fanatic. As I started to grow more mature in my reading, Steven’s influence flexed its grip, and I began reading Stephen King as well. Although I’ve read several of King’s novels – including the massive undertaking “The Stand” – I’ve never attempted his series of novels “The Dark Tower.” This all changed when I got a haircut two weeks ago. Steven said he had something for me, and then brought out a bag from Pei Wei filled with the first six books of “The Dark Tower” sequence. Although the bag weighs at least twenty pounds, without representing the entire text of the series, I dove right in, beginning (obviously) with the first book of the series (which is, coincidentally, by far the shortest).

“The Dark Tower: The Gunslinger” begins the epic quest of Roland, the last Gunslinger. As we meet him, he his chasing “the man in black” across a desert in some sort of western-fantasy world. Apparently, Roland has been chasing him for a long, long time and has very recently been catching up. In the first part of the novel, Roland walks into a trap the man in black has set up in a know-nothing town, and the only way out is to, quite literally, kill every person in the small city (including his own lover). Further on, at an abandoned way station in the desert the Gunslinger encounters a boy – Jake – who apparently died in our world (at the hands of the man in black) only to re-awaken in Roland’s world. The Gunslinger allows Jake to join his quest, and the two miraculously cross a seemingly endless desert to arrive at the mountains – with the man in black now in sight. The pair encounters a malicious oracle who suggests that Roland will have to kill the boy if he wants to catch his quarry. As Roland and Jake pursue the man in black through the caverns of the mountain, they are attacked by Slow Mutants (human like creatures with distorted features who glow in the dark) and narrowly escape. With the cavern’s exit within reach, the man in black blocks their egress, and Jake clings desperately to the side of a rail-bridge. Roland has to choose between the boy and the man in black and, painfully, chooses the main in black. The novel ends with the man in black revealing that their dying world is just a single grain on a piece of grass in an even larger universe – all part of an infinitely large and small chain of worlds. Roland is set off on his quest to find the Dark Tower (a nexus between the many worlds) and to face off against The Beast who guards it.

Of course, that’s all merely the main story. Through the course of a few flashbacks and “firelight stories,” we learn a lot about Roland’s past (though many mysteries are also raised in the aftermath). For example, we learn that he grew up in highly regimented and caste-regulated society. This court resembles, loosely, Arthurian legends, although the noble knights are replaced with gunslinging cowboys. Yet, sometime between Roland’s childhood and the “present” of the novel, there has been a devastating war and that world is “dying,” leaving Roland as the last true Gunslinger. There are lots of references to Roland’s father being cuckolded, a vicious trickster named Marten, and a beautiful woman named Susan – but these references remain murky.

The world that King establishes in the first of “The Dark Tower” books can be best imagined as a hybrid between Clint Eastwood’s early westerns (lots of isolated towns, desolation, dirt, and sweat) and King Arthur’s court (class structures, knights and maidens). This comparison is practically invited by the reference to a wizard from our world named “Maerlyn” (think: Merlin). There are also elements of traditional quest stories and poems – notably “The Odyssey” of course. Also, apparently the name Roland is a reference to a Robert Browning poem (but, at this point, I’m too lazy to care about the allusion beyond what is mentioned in the afterword to the book).

There is a strange connection between our world and Roland’s world. The boy Jake somehow leapt between the two worlds. A gas pipe at the way station in the middle of the desert seems to connect the two worlds. There’s even a strange subway-like terminal that Roland and Jake walk through in the middle of the caverns of the western mountains – although the remains of those working at the station have apparently been dead for a very, very long time.

Our protagonist – Roland, the last Gunslinger – provides an interesting point of discussion. He is not necessarily sympathetic – heartlessly choosing his own ambition over saving the boy Jake. Yet, at the same time, we find it hard to judge him. Although we quest with him for 216 pages (at least, in the edition I read), we hardly get to know him. Sure, we know that he was the youngest boy ever to earn the title “Gunslinger” and that something bad went down between Marten (the man in black’s master) and Roland’s father – but, to be honest, that’s all we really find out. We never even quite find out why he’s chasing the man in black – and that goal alone makes up the main conflict of the novel.

Considering that there are at least six more books in this series (more, if King keeps adding to the epic), I’m finding it hard to judge here the value of the entire sequence of novels. Ultimately, “The Gunslinger” provides mere exposition for the longer series, while also allowing us a little glimpse into this strange (but fascinating) universe. I just hope that the rest of the series picks up the pace a little bit, because “The Gunslinger” was painfully slow at parts. At the very least, I can see how “The Gunslinger” provides a lot of food-for-thought for a fantasy reader and gives a rich and unique universe for Roland to wander through on his quest for The Dark Tower.

(The next book in the series: “The Dark Tower: The Drawing of the Three”!)

Monday, January 18, 2010

Avatar

Friday, January 15, 2010

Everyman

Sunday, January 3, 2010

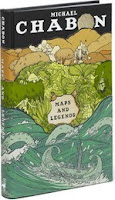

Maps and Legends

The first edition of Michael Chabon’s “Maps and Legends” – put out by the great McSweeney's Publishing in 2008 – has perhaps the most interesting cover I have ever seen. The actual hardcover volume has several colorful and uniquely decorated paper dust jackets, each a little smaller than the one underneath, which are spread so that you are able to see a bit of each at the same time.

This opening invitation to inspect and look at each intricate dust jacket, each as its own cover and as part of the larger cover artwork, is a metaphor that can be extended to the contents of the book. Each essay can be read as an individual piece of writing, or as part of the larger book.

It would be irresponsible for me to describe each individual essay of the book instead of encouraging you to savor them yourself, so instead I’ll stick to discussing the larger themes and highlighting a . (Truth Time: It would be TIME CONSUMING for me to describe each essay, and I’m feeling very, very lazy).

The title essay describes Chabon’s childhood fascination with enterprising through his neighborhood and planned wilderness (he practically had a forest for a backyard), and then creating personalized maps for the area. Although my own childhood took place in a grid-structured suburb which left little to actually be discovered, I was still able to relate to the childhood urge to explore, to find and expand boundaries – both literal and metaphorical.

These ideas of adventure, exploration, and boundaries are the central theme of the book, even when the essays are ostensibly about other subjects.

For example, one piece consists of a book review of Cormac McCarthy’s novel “The Road” (reviewed here earlier) but much of the work attempts to define the “borderland” between genre-fiction and “serious” fiction that McCarthy’s masterpiece inhabits. Another part seems to be an extended review of Phillip Pullman’s “His Dark Materials” trilogy (which I still haven’t read, and, somehow, lack even a sliver of an urge to read), but really questions the nature of the ever-hazy Young Adult form of literature. There is even an essay about the history of Sherlock Holmes which leads to a discussion of the history of fan fiction and fan fiction’s place in the halls of literature. (There are, of course, parts on the relevance of comic books - one of Chabon's recurring subjects.)

The biggest pitfall of the book is that several of the essays center their argument around very specific subjects (such as Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road”). If you do not have the requisite background knowledge, reading these chapters can be like wandering an unfamiliar city without a map (if you don’t mind me using the map metaphor). This is not to say that these parts are not enjoyable, but just that it can be harder to find the intellectual landmarks which make them interesting. (In the language of teaching - which I am occasionally wont to use - cultural capital makes the book understandable.)

Ultimately, in the spirit of the work, I’m going to encourage you to have an adventure – take a jump, explore the book, and make your own map!